You wait a whole year for a Virtual Reality endurance attempt, then three come along at once.

Derek Westerman spent 25 hours in a virtual room drawing with Tilt Brush, a 3D creative tool designed to allow the user to build VR sculptures. Result: He set a Guinness World Record, babbled incoherently and threw up in a bucket.

Next, Alejandro “AJ” Fragoso and Alex Christison spent 50 hours sat on a sofa, eating snacks and drinking Red Bull watching TV and movies on Oculus Rift headsets. Result: They too grabbed a record, suffered with indigestion and grew beards.

Don’t get me wrong, I love Guinness World Records and I have a long and happy association with them. However, Virtual Reality is saddled with an image problem, one of nauseating game-play and fellas mostly wasting their time. Sadly, these types of endurance records reinforce it.

If I sound less than impressed with these other attempts, it’s because I am. I spent 24 hours in VR last year (but that’s another story) and this year, as much as I wanted to tackle the official 48 hour VR record, GWR insisted we stay awake for the entire two day period and this ironically wasn’t realistic.

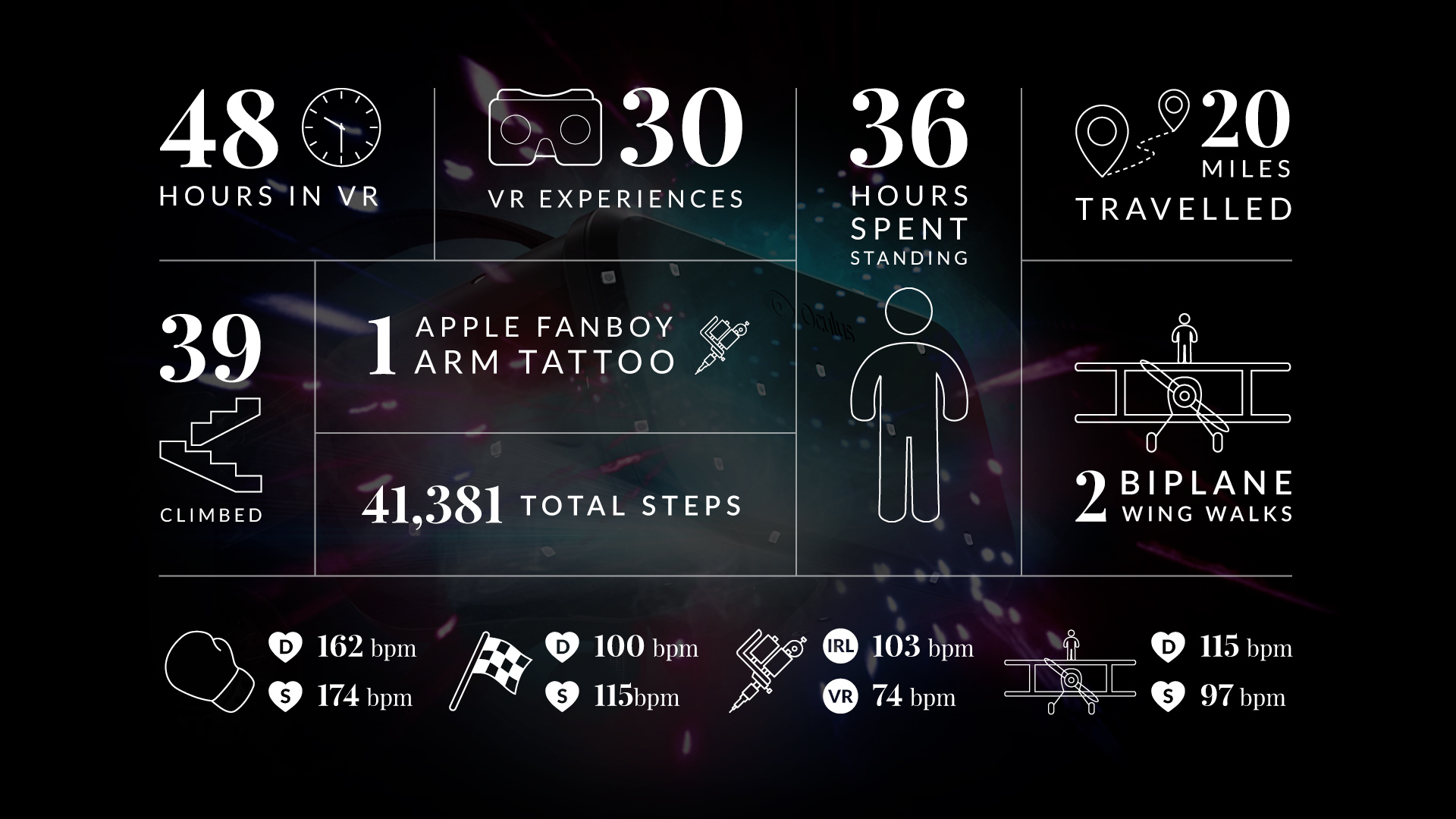

I joined forces with Sarah Jones, a senior media academic and 360º storyteller, to ‘live’ in Virtual Reality. This included eating, sleeping, running, fighting, driving, wing-walking, even getting a tattoo! Everything we tackled, we did so for a reason, not just because we could but to show the outside world that VR has a place in our lives and is there to complement it, rather than replace it.

We harvested meaningful data, relayed anecdotal feedback throughout our experience and 5 minutes per hour were reserved for dashes to the bathroom and 360º video diaries – not at the same time I hasten to add.

Amongst the more conventional VR experiences such as problem-solving, training, painting and gaming, we scheduled three extreme physical activities. Our first required us to drive go-karts around a purpose-built track, using the through-camera on a Samsung Gear VR to give us a video view of the surroundings. An interesting challenge when the vibration of the vehicle causes the camera feed to shake and blur, but a great illustration of driving on instinct and highlighting some genuinely useful user-cases for Augmented Reality headsets.

Race info, ghost competitors and screen entertainment for autonomous vehicles will all follow as a direct result of this kind of real-world testing.

Our second physical challenge required less movement but greater immersion. I was ready for my tattoo…

I haven't been under an inked needle before so this was my first taste of body art. I have to admit to being a less than enthusiastic volunteer but we were determined to discover if VR could successfully mitigate pain. The irritation needed to be sustained and relatively intense, so leg-waxing or nipple-piercing were out!

I chose Gunjack to keep my mind off the job in hand (or arm). This 3D space adventure requires a pretty low skill level, but quick reflexes and prolonged concentration.

I began the process with my headset up, allowing me an unimpeded view of my arm as the needle struck home – my baseline pain levels were set. If I were to describe this raw tattooing pain as a sustained maximum of 10, I felt the VR content and the subsequent cocktail of endorphins and adrenaline genuinely dropped the irritation to a 6 or 7. That result alone would have satisfied us but we were also wearing Apple Watches throughout VR48 to monitor heart rates. Mine peaked at 103BPM in the tattoo studio with a clear view of the procedure, dropping to 74BPM under immersion. That’s anecdotal feedback supported by real science.

Sarah and I returned some uniquely different results over the course of the two days and nowhere was that more evident than in our ultimate challenge – the wing walking finale.

Still wearing our VR headsets, we arrived at RFC Rendcomb Aerodrome at 10am, fresh from the journey from Coventry University to Cirencester in the back of a MINI Convertible – acclimatising ourselves to the freezing temperatures and buffeting we’d have to endure at 150mph when strapped to the top wing of a 75 year old aircraft.

With all our preparation, our additional webbing, straps and a bespoke balaclava weren’t enough to satisfy the experienced pilot or the Breitling Aerobatic team – we were told to hold onto the Gear VR headset with both hands for the entire flight. There would be no waving to the crowd mid loop.

We hoped to gain valuable insight into the effects of velocity and wind resistance on VR viewing. Could reality enhance the virtual experience and vice versa? To view this, we would again be seeing the real world through the Samsung headset’s built-in camera. Or would we?

I mentioned different experiences and mine took a turn for the worse when strapped to the wing, preparing to taxi to the far end of the airfield. “Please remove your phone and update the software”. Seriously? My Galaxy Note 4 had chosen this very moment to force a software update on me. I wasn’t asked politely if I would like to – just told it would happen or my phone was dead. With no adequate connection in the middle of a field, I was faced with a useless piece of technology.

Not willing to submit to the failings of the Internet of Things, I removed the phone and squinted through the headset lenses for the duration of the flight. Not all was lost, as I actually experienced this through the eyes of a partially-sighted individual. Chalk one up for the power of empathy, and a huge black mark for Samsung.

Sarah had no such problems as the team set up a wireless hot spot, updated the software and sent her off to view the entire flight as planned – with the valuable research recorded.

One of the surprise results of VR48 was our time spent in Knockout League, a boxing simulator for HTC Vive and Oculus Rift. Your opponent is a larger-than-life cartoon character but the gameplay feels every bit as real as time spent in the ring with an actual heavyweight. We found ourselves ducking and diving, with adrenaline levels and heart rates increasing as our (virtual) vision blurred from a flurry of head-shots.

If ever there was a case against stereotypical VR couch potatoes, virtual boxing was it. That and the go-karting. And the tattoo. And the wing walk.

So what were the side-effects? For an endurance attempt such as this, it can be difficult to differentiate between regular eyestrain and fatigue and that relating to being in a virtual environment. Sarah’s forehead was sore and her cheeks were temporarily marked. The bridge of my nose was bruised and my close-up vision is still slightly more blurred than before the event.

Other than that, we appear to be psychologically unaffected – even with our VR48 content planning requiring us to fall asleep and wake up in VR!

This medical research may come as a surprise to the public, brands and hardware multinationals alike as I’m pretty sure they all thought we’d be lucky to survive unscathed.

We received no support from any headset or mobile manufacturers as they believed we contravened all their health and safety advice, but these side effects are never talked about at the many global industry events and certainly not in the consumer press.

I hope we've gone some way to change the current perception of VR and to highlight its potential, rather than its shortcomings.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Huffington Post